It would begin at around 4:45am. The staccato chanting of the priests, overlaid with a sonorous narration of the history and significance of the shrine. The deity is being decked up with flowers, layers upon layers of them. Look how regal he is, the narrator says, look at that that enigmatic smile, look at all the devotees chanting in unison, some with their eyes closed in prayer, some straining to get a closer look. In a few minutes it would reach a cresdendo - the cymbals striking, the bells clanging, the chants rising in fervor, the narrator jumping into high pitch. ‘Vinayaga!’, ‘Narayana!’, ‘Siva Siva!’, ‘Madhava!’. The bedroom doors would open, and we - my brother and I from our shared room, my parents from the master bedroom - would totter in to the drawing room. My grandfather would be seated on a chair pulled extremely close to the television but perpendicular to it, so that his right ear could be placed as close to the screen as possible. His back ramrod straight, with not a wrinkle on his white veshti, the television tuned (on the highest possible volume) to one of the early-morning religious programmes on the Tamil channels, his eyes partially closed in focus and enjoyment, his palms tapping out the rhythm against his thighs, seemingly oblivious to the yawns and scowls of the family that had now surrounded him. ‘Reduce the volume, thatha!’ my brother would say, before taking the remote and punching on the button a few times. My grandfather would ignore this and continue gazing into the distance, slightly amping up the tapping of his thighs, with the hint of a cheeky smile on his face. Thus would our days begin.

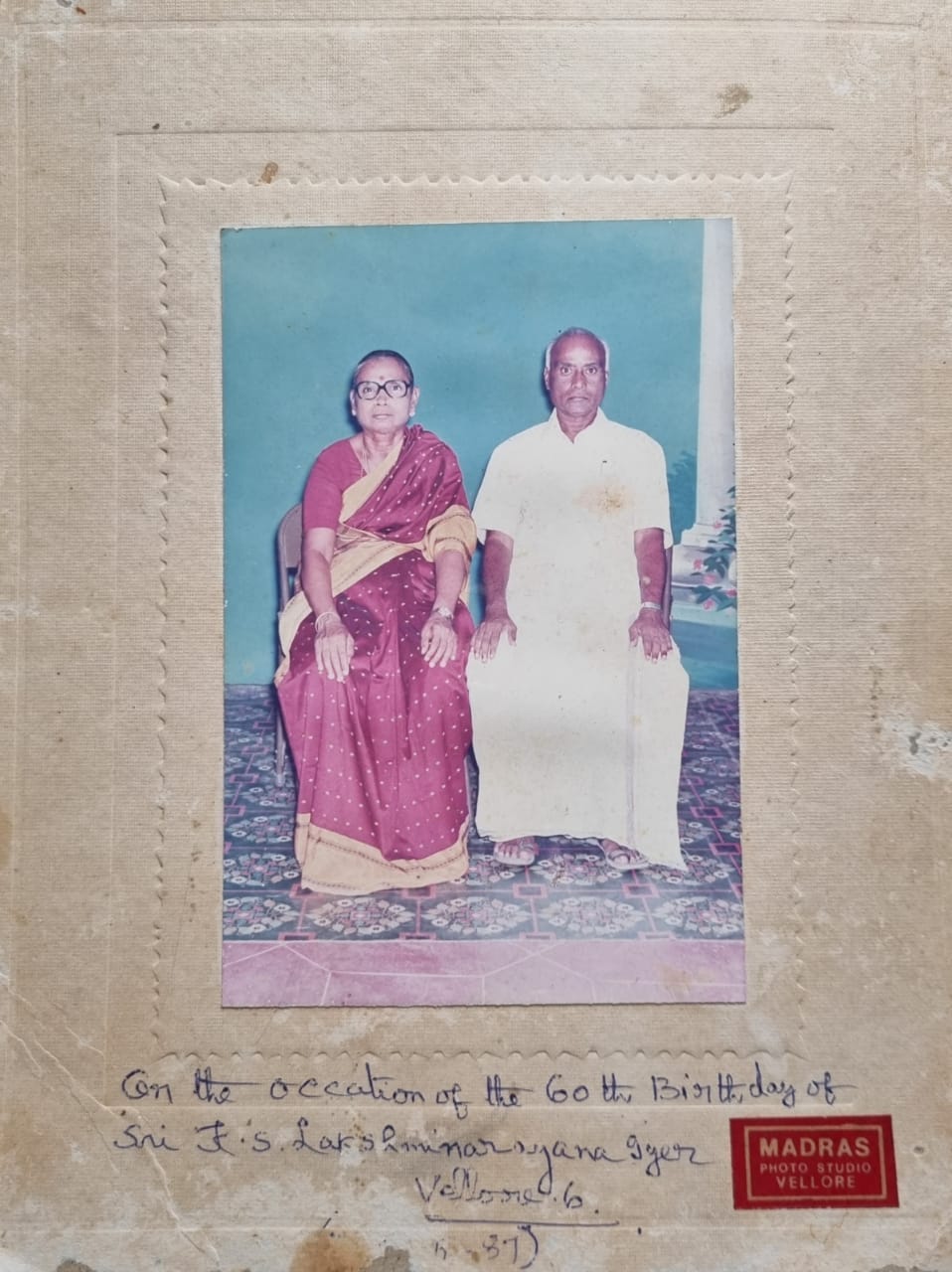

My grandfather K.S. Lakshminarayanan was a unique personality, with some aspects that were admirable, some that were off-putting (or infuriating), some that were hilarious; it is hard to pin him down. Instead of making broad character summaries, then, I find myself recalling vignettes from our time with him. Oh there are so many that readily come to mind.

When one thinks of thatha, one thinks of him walking. One thinks of him getting ready to walk, his half-sleeved cotton or khadi shirt starched and ironed until it was stiff, his veshti spotless, his forehead packed with sacred ash in three thick and exactly parallel lines, a yellow cloth bag (which would be empty when he left home, filled with Tamil magazines and snacks when he returned) by his side. And off he would be, without a word of leave.

Where would be walk to? Wherever his fancy took him, but mainly to temples. Large temples, tiny hole-in-the-wall shrines; popular temples with huge lines of people waiting to get in, practically unknown ones where he could talk with the priest at leisure; Shiva temples, Vishnu temples - they were all of equal interest to him. If it was anywhere within fifteen kilometers, he would walk. Starting at around 4pm after his afternoon coffee, back at around 8pm in time for dinner. I accompanied him on some of these rounds, invariably stopping on our way back at an Udupi restaurant for a sambar-vada or a plain dosa. As the years went by and his health deteriorated, the doctors placed quite severe restrictions on his diet; the 'no sweets' part of the instruction was not much of a deal for him, but he had a tongue for the tangy and the spicy, and these evening detours were his way of getting his snack fix (which was denied by my strict grandmother at home). We grandkids had an unsaid pact with him, that what happens during these walks stays outside of the home. We got our chips, dosais and samosas in return, so we gladly kept silent.

My grandmother tells me how their days would begin, back when they were a young family. Paati was a government school teacher in Vellore; she taught almost everything to primary-middle school students, but her focus areas were Tamil and Mathematics; she was my father’s first class-teacher. Thatha was a sales representative in the government Khadi department. Paati would scramble to get the four children ready for school - making breakfast (thatha would help a little bit by cutting vegetables, scraping coconuts), fetching water from the well and heating it up with firewood, getting the kids bathed and dressed, packing lunch for the kids and her husband, getting ready herself. And then she would head out with the kids in tow towards the school, while my grandfather (yes - khadi half-sleeve shirt, veshti, yellow cloth-bag with lunch) would head out in a different direction to make his sales visits. He would walk. There would be some bus rides on the way, but most of the time he would simply walk (the bus fares were not always affordable by my grandparents at the time). From one stop to another, under the relentless Vellore sun, thatha would walk.

One of the most dispiriting things to see is a person in the final of their life being denied something small, something simple, that gives them so much joy. To catch my grandfather glancing hungrily at our banana leaves laden with the numerous components of a traditional feast, while his leaf was missing all the doctor-disapproved (i.e. the tastiest) items, to see the childish yearning on his face, was unsettling. Here was a man who had lived a long, hard, and eventful life, who had pushed through severe financial difficulties to raise four children. In the final years of his life he should be able to do as he desired, be answerable to no one. But here he was, looking sideways at our leaves, very obviously craving for what was on it, perhaps shattered by the knowledge that he might never again be able to have one of these full-course meals that he so cherished. I shouldn’t let this happen to me, I would tell myself, as I pushed through the guilt and tucked into my meal - when I am old, I will do whatever it is I want to. Or else, I told myself, I will get myself to the point where I don’t crave anything, where there is nothing the lack of which will cause me pain. But on this latter point I knew I was kidding myself; there would always be something that brought joy, something that we looked forward to every day - and when that is taken away, the hole is filled by a dull and ever-present frustration. It is one thing to let go of something of your own choice, quite another thing to have it snatched away. My grandfather, after all, gave up potatoes (something that he really liked) on one of his visits to Kasi/Varanasi. He was a man of very modest means and a narrow range of tastes. He was not seeking luxuries, he did not wish to travel the world, he was not curious to sample exotic cuisines, he did not get excited by new clothes or gifts. All he wanted was to be able to travel to temples in India as long as he was physically able to, and to dip his finger into some puli-inji1 from time to time. And he was denied both of these things. His eldest son - my father - was quite firm about him not traveling, about observing his strict diet; with good reason, of course - he cared deeply about his father’s health. But I wonder, if in seeking to extend his live by a few more years, whether my father ended up making those years just a little less filled with happiness for thatha? I don’t think so. Thatha knew all the things his son was doing for him; he knew that while his son’s communication style might at times be brusque, everything he said or did was with thatha’s best interests; he perhaps knew that behind the steely exterior there was the concerned, worried, caring son. So yes, thatha knew that what he was giving up was insignificant compared to what he was getting - the concern, love, and support of his children, his wife, his extended family. But, well, he did miss his puli-inji and vathakozhambu2.

He was a village and small-town man, with a very rustic point of view on most things. Some of his attitudes could be disturbing to the urban born-and-bred like me, some amusing, some very enlightening. But what comes to mind now are some of his aphorisms and his trademark coinages. One that I love is Se-Koo-A-Ku, short for seththa kooda azha kudaathu. It is very hard to translate this and carry over the flavor, but loosely - ‘you shouldn’t cry even if you die’. I said ‘you’ die (which makes it seem more cryptic that perhaps needed), but the ‘you’ isn’t specified in thatha’s original. Just seththa kooda azha kudathu; se-koo-a-ku. A darkly Stoic sentiment, I suppose, in the irreverent Lakshminayaranan style, usually muttered by him with a chuckle.

He might have been small-town man but he had larger visions for his children, especially his eldest son (my father), who had been earmarked by everyone in the family as a brainy child. It was thatha who read - in The Hindu - about the admission tests to the Indian Statistical Institute that were to be held in Chennai, and immediately registered appa for it. Neither of them had even heard about ISI Calcutta prior to that; all thatha knew was that his son was gifted in mathematics, and from his little bit of asking around he gathered that this institute seemed to be highly regarded. He escorted my father along to the entrance test, and (with paati of course), pulled together all the finances they could to send his son off to faraway Calcutta. The years at ISI - the friends he made, the new languages (Bengali and Hindi) he learnt, the experiences he went through - broadened my father’s horizons and gave him the platform he needed to start shining. Appa has expressed to the rest of us, in many different ways, how grateful he is for this early push from thatha.

But of course he is not the type to actually say the words ‘thank you’ to his father; the mere thought of the two of them having such a conversation tickles me.

Thatha was the one who took me to my first day of formal schooling in India (after my parents and I moved back to India from the US). My mother, father and grandmother got me dressed up in the new school uniform (which was a tad short for me) and packed my backpack and lunch basket, while thatha waited patiently. We have a picture of me, taken just before I stepped out of the house. I walked over to the school with thatha, clutching his hand. Everything seemed smooth. But as I neared school, I started to feel restless, scared. I wanted to go back home, to the safety of my parents. I started protesting, begging thatha to take me back. He pulled me along. I cried the entire last stretch to school. Because of all my protesting, all the cajoling (and threatening) that thatha had to do to get moving, class had already started when we got to school. I cried all the way up the stairs, I cried as I walked into the classroom, I cried as I introduced myself to the class, I cried as I sat down. I remember looking at thatha through the classroom door, trying desperately to hold on to his image as the door shut.

Growing up, and even as an adult, I have always had to struggle with change. Each time I moved between cities or schools, I was some version of that kid on my first day to school - protesting against the change, seeking the comfort of stability. I don’t think I spoke to my thatha about his experience taking me to school that day, about my tantrum and how he dealt with it. But if I did ask him, I can guess what his reply would be - se-koo-aa-ku.

He had a hearty disdain for all things ‘Western’. He didn’t approve of girls wearning vella-kaara3 dress (shorts, pants, and the like), in fact he didn’t approve of boys going too much in that direction either. If he had his way I would always step out of home with a full pant (no silly things like shorts), a proper shirt (t-shirts for him were a vella-kaara abomination) with even the top button fastened, hair slightly oiled and combed with a clear partition, and vibhuthi on my forehead - preferably three robust lines of it, but he could make peace with one small dash. Anything short of this would be clucked at by him as vella-kaara attitude. Up to his very last days, when I came down after a bath, he would look at me pointedly for a second and say ‘your forehead is missing something’. And if I turned away without heeding to it, I would hear a sigh and a mumble (‘vella-kaaran…’).

He was even more particular when it came to food. He didn’t like anything apart from proper Tamil Nadu vegetarian food. No experiments. He didn’t even approve of the Palakkad-style food of my mother’s side of the family. North Indian food was just something he had to put up with since he traveled widely to temples across the country. And let us not even get started on vella-kaara food (he looked at the pizzas we ate with mild disgust). You couldn’t even get him to eat a slice of bread, which he called pulla-peththa rotti. The story behind that phrase? When he was growing up in rural North Arcot, the only time anyone got the luxury of eating bread was if they were mothers who had just delivered a baby. A few slices of white bread would be given to them for energy. Hence pulla-peththa rotti (roughly - roti for those who have given birth). For the life of him thatha couldn’t understand how anyone who had not recently delivered a human would voluntarily put bread into their mouths.

Towards the end of his days, with most spices taken away from him, there were times when he had to make do with a few slices of pulla-peththa rotti. My grandmother must have felt terrible giving him slices of bread and milk, but we didn’t have a choice. Life can certainly be cruel. I’m sure thatha would have silently muttered a robust native cussword or two before picking up his first slice.

My grandmother tells me that their family - herself, thatha, the four children - would often pack up and head off to temples around South India even back in the day, when my father was a child; but my grandparents’ almost-perennial travels around the country began when they both retired from their government jobs. They shared a long-standing desire to visit all the temples of India (or as many as they could) - driven in equal parts by devotion, curiosity, and love for travel. With comfortable government pensions month-on-month, and kids settled down and busy with their own lives, they could finally jump into their journeys in earnest. From Kedarnath to Rameshwaram, from Somnath to Jagannath, and everything in between. They would read about a temple in one of the Tamil weekly magazines, and would immediately start planning the itinerary. A few days later (at most), off they would be to Katpadi station, to board a train to some far corner of this vast land. The rest of us would find out about their travels later, once they were back home in Vellore; sharing their plans too early - especially as they got older - would mean having to deal with my father’s concerns. And my father is certainly not one known for beating around the bush with his communication. Thata didn’t want to risk it; and his wife was more prone than him to see the sense in their son’s words - he didn’t want her to have a change of mind. So he waited till they were back, and would then write a long letter cataloging their journeys. Or sometimes he would send the letter off just before they embarked on their journey, dropping it in at the post box on the way to the train station. He would fill every inch of one of those blue-paper inland letters (haven’t seen one of those in more than 10 years; are those still around?) with his distinct, calligraphic handwriting. Sometimes in English, sometimes Tamil, sometimes a manipravalam-like hybrid of the two. He had an archaic way of writing, part due to his schooling in British India, part due to him being him. ‘Dear Ravi, I am writing to apprise you of the following events. Your mother Shenbagam and I have just returned from a trip to Badrinath…’

I can only imagine the number of stories that they would have collected from all their pilgrimages. Note to myself: I must sit down with paati and ask her to walk me through her memories - it might turn into a mini encyclopedia of temples in India. (They would bring a small idol with them - that would be placed in the puja corner at our place - from each of their visits; over the years the puja room was overflowing with these idols). But I am also interested in learning about all the things that must happened beyond and around the actual temple visits. About the people they met on the way, the challenges they faced, the food they ate, the places they stayed. What did thatha and paati talk about on those long train and bus journeys? Were they able to leave all their tensions back home when the boarded the train at Katpadi junction? Were there some moments of silliness between them, did they share a laugh or two?

After they moved in to live with us, though, they obviously couldn’t just pack up and head off. And neither thatha nor my father enjoyed the long and vexed conversations about the risks of long train journeys at their age; thatha knew that he would lose out in these arguments. But he still wanted to travel. So he would write a long letter on an A4 sheet of paper. He would then walk in to the living room when the family was watching TV, very conspicuously drop off the folded sheet of paper on the coffee table in front of us, and then walk away without a word. My mother would open it up as my father grumbled. ‘Dear Ravi, I am writing to seek your opinion and permission on a matter of great interest to your mother and father. While perusing the magazine Kumudham I came across an article about a new puja service at the Pashupathinath temple in Nepal and..’.

‘Appa!’ my father would scream, without completing the letter. But thatha would have closed the bedroom door behind him by then.

I sometimes wonder how he would have reacted if he were around to meet my wife Charanya. Not only does she wear vella-kaara clothes quite often, she is quite outspoken about most things and - most disturbingly for thatha perhaps - she enjoys gamely teasing my father, playing pranks on him, pulling his leg; whereas most of my extended family treated appa with a certain amount of deference. Would it have been too much for my grandfather to stomach? Would he have pulled me aside to have a word or two on my choices in life? Would he have squinted at her with his mouth full of his favorite veththalai and kotta-paakku, trying to decipher this new specimen in the family? Perhaps. But there’s also a chance - after the initial shock wore off - that they would have hit it off. Apart from the vella-kaara side Charanya also has a very traditional side - she might wear shorts but she is also very comfortable in her sarees; she has a keen interest in temples and the history and folklore associated with them. I can visualize her engaging thatha in long conversations about his temple visits, getting him to open up and share in ways that the rest of us had not been able to. Perhaps they would have teamed up to play pranks on my father. Perhaps. One will never know.

Thatha’s Hindi - honed by all his travels in the North - was not too bad, but it was heavily accented (of course) and came packed with many quaint terms and phrases that one associated with a Doordarshan broadcast. My own spoken Hindi - even though I learned it formally in school and watched a lot of Hindi movies - wasn’t too much better either; it got the job done, that was about it. The two of us, though, had this ridiculous habit of randomly slipping in and out of Hindi in the middle of an otherwise normal conversation. Picture the scenario: fix or six of us seated around the dinner table discussing something serious; suddenly, thatha addresses me in his formal Hindi; without batting an eye-lid, I respond to him in my own Hindi, and we - very earnestly - keep the dialogue going for a good few minutes as the others patiently wait for the silliness to end; and then one of us slips back into Tamil, and we continue as though nothing untoward had happened.

It is now eleven years since thatha passed away. He would have been 93 today. As family, what we can do is to remember him, to share our stories about him. Not just the sanitized, happy stories but everything - the impact he has had on our lives, his eccentricities, his stubbornness, his rage, his impish humor. As long as he lives on in our memories, he continues to be with us. We shouldn’t let the memories fade.

I don’t know where he is right now, but I hope he is finally able to throw away all health concerns and tuck himself into a full-course meal whenever he wants, before heading out on a long walk, to wherever the road takes him, setting aside all his worries, with his yellow cloth-bag by his side.

https://www.saffrontrail.com/puli-inji-ginger-tamarind-chutney-recipe/

https://www.subbuskitchen.com/vatha-kuzhambu/

‘white man’

Was a nice Sunday morning breakfast read!

Reminds me of my paternal grandmother, who shared a lot of similar traits - a penchant for visiting all temples (she managed to check pretty much everything off of her bucket list), her longing for sweets after they were taken away from her (she used to look forward to those Lindt chocolates I would get for her whenever I visited her), and being very orthodox (although she ‘opened up’ with age, realizing her own inability to follow some rules).

My grandfather passed away when I was four, so I don’t remember much. It was my grandmother who took a crying me to the first day of school, shared a brief but a special bond with my wife (they didn’t even have a common language), and was the chief story teller throughout my childhood.

This post helped recollect some of those memories, thanks for sharing!